3D In Every-Day Life:

Four Reasons Why It Didn't Work Earlier

(And Why It Could Work Now)

If you are working in a business, or in a research institution, which is related to 3D graphics, you may know by now that we can render beautiful 3D graphics within common Web browsers, using WebGL.

For several years already.

You may also know that there are platforms like Sketchfab, enabling users to easily view, upload and share 3D content - pretty much like what YouTube does for videos.

Finally, you may know that we as a 3D graphics community have even figured out a common format for efficient exchange of ready-to-render 3D assets, which is glTF.

If your work is not related to 3D graphics, however, chances are high that you didn't hear any of these names before.

And, much more critical, chances are high as well that you never made use of 3D graphics at all, apart from maybe games, during your every-day life - although you probably use your Web browser every day, or most likely at least several times a week.

Exciting 3D Content on Sketchfab.

If an expert who is working on 3D on the Web is asked what she or he is doing, the explanation often seems surprising to someone who is not familiar with the field. This especially applies when you're not working on 3D games. Ideally, you will get answers like "So you visualize shoes or ancient vases online in 3D? That's cool. I didn't know that this is possible." But maybe, especially when you talk to your older family members, the answer may be another question, such as: "And you can live from that? Are people really using this?"

Apparently, when it comes to things such as 3D retail applications, there is still a - very large - gap between what is technically possible and what has been adopted by real-world applications out there.

In fact, let's be honest:

Apart from games, almost no one uses 3D visualizations within daily life. Period.

Of course, one exciting question in this context is:

What will happen in the near future?

Could 3D content, after all, really become a part of our every-day online life, through common applications such as shopping, advertisement and education?

A 3D Shoe On The Web

As a PhD student working on 3D graphics topics, I am certainly having an inside-out point of view on this topic. I remember that, around one year ago, I was talking to a great 3D expert, who had many years of experience in the field. We were discussing a 3D visualization of a shoe inside a browser, and he had to laugh a bit when he first saw it. After I asked why, his response was: "This is something 3D folks were talking about for a long time, always hoping that people would really soon buy their shoes in 3D on the internet." There was a notable amount of wariness within that statement. And that leads me to the central question of this article:

How are the chances that we see a significant increase in 3D applications within our every-day life, within the next five years?

A shoe. Not 3D, but on the Web.

Right now, one year after the 3D shoe experience, I just started to write the introductory chapter for my PhD thesis.

And that made me think about the practical relevance of my work for the majority of society - people that do not use 3D visualizations within their every-day life, yet.

Obviously, technology is moving forward quickly. And in contrast to ten years ago, many people do already, in fact, buy shoes on the internet nowadays. As a German, I am directly thinking about Zalando, for example - a company from Berlin, founded in 2008, which is selling shoes and other clothing online, having a revenue of over 3 billion EUR in 2016.

Be it a commercial application like 3D-assisted online shopping,

or be it the world's cultural heritage made accessible to everyone for education purposes:

like probably most people working within the 3D graphics area, I would be happy to see more real-world 3D on the Web.

Within this article, I am trying to motivate why I believe that there are really good chances that we see a significant increase in usage of 3D content for every-day applications that are not games, within the next five years. One could argue about this point by discussing why one would (not) want to have 3D visualization at all. That, however, is a basic question I wouldn't like to argue about right now. Instead, within the rest of this article, I will motivate my positive statement using four arguments that explain why it is only logical that the mentioned increase in usage of 3D content didn't happen earlier - and, consequently, why I believe it is quite possible that we could see it within the near future. As you may guess, I am naturally biased at this point, therefore I am very thankful about any kind of feedback - especially the critical one.

Four Reasons Why It Didn't Work Earlier (And Why It Could Work Now)

Throughout the past few decades, experiencing 3D scenes through Desktop screens or VR devices has often been regarded as a natural extension of 2D experiences through static images or classical video, with possible applications in different many fields. However, until a few years back, 3D content, apart from video games, was usually not accessible for non-professional users. This was mainly due to four different reasons:

- Hardware & Software Capabilities.

3D real-time renderings did not provide the desired degree of realism to be suitable for purposes such as online 3D retail applications and remote 3D inspection.

- Hardware Availability.

Powerful 3D graphics processors (GPUs) were only available as dedicated hardware for Gaming PCs or consoles, and VR hardware was not affordable for non-professionals.

-

Software Availability.

Interactive 3D visualizations required special, system-dependent software, which was usually not pre-installed on common PCs. -

Difficulties with 3D Interaction.

Since they were rather uncommon in every-day-life, interactive 3D visualizations were usually found difficult to use for most people.

Thanks to several technical trends that emerged during the past decade, all these limitations have mostly vanished by today.

Hardware & software capabilities have drastically increased over the past two decades. Since the first real 3D games emerged in the mid of the nineties, the game industry has been constantly pushing the limits of what was possible with real-time 3D graphics. Demands for a high degree of realism, appealing visual effects and high frame rates have led to the development of powerful graphics hardware and highly efficient real-time rendering algorithms.

Hardware availability is guaranteed through modern Desktop PCs, laptops and even smart phones, which are nowadays all equipped with relatively powerful GPUs. In addition, even VR hardware is becoming increasingly available to everyone. Smart phones, which are usually also equipped with cameras and gyroscope, can already serve as rendering and tracking devices within specific VR headsets, leading to a drastically increased availability for simple VR setups.

Software availability has become less of a problem since the advent of WebGL. Suddenly, everyone with a Desktop, Laptop, tablet PC or smart phone can directly access 3D content inside a common Web browser, which is usually pre-installed and also available for free for all kinds of platforms. In addition, Microsoft has just made some significant steps with its 3D For Everyone strategy: the latest Windows 10 creator's update provides a 3D version of Paint, familiarizing Windows users with basic 3D content creation, and 3D files in glTF format can simply be opened within a 3D viewer that already comes with the system. Also, 3D content is consequently made available as a new medium within the Microsoft Office software, which enables users to show a 3D scene as part of a slide show, for example.

Difficulties with 3D interaction are increasingly being overcome, through changes on both sides of the table: On the side of the users, a generations that nowadays consists of middle-aged and young adults, born in the late seventies and in the eighties, have been the first to grow up playing 3D video games. Younger generations are even more confronted with interactive 3D content as part of their day-to-day life. Interacting with a 3D object, for example as part of an online retail scenario, has therefore become a less unusual, or challenging, experience. On the other side of the table, researches and practitioners have developed a lot of helpful and intuitive methods and best practices for 3D interaction. Dedicated university programs on Human Computer Interaction and the availability of professional expertise within this area actively help to make 3D content more accessible to everyone, even - and especially - to non-experienced users.

A Simple Example

As a consequence of the great technological achievements within the past few years, highly appealing 3D content is already becoming publicly available to everyone. And I currently believe that, this time, there are really high chances that these technical offers will be broadly adopted by a large group of non-expert users, enabling novel 3D applications in every-day life. Let's have a look at the following, very simple example:

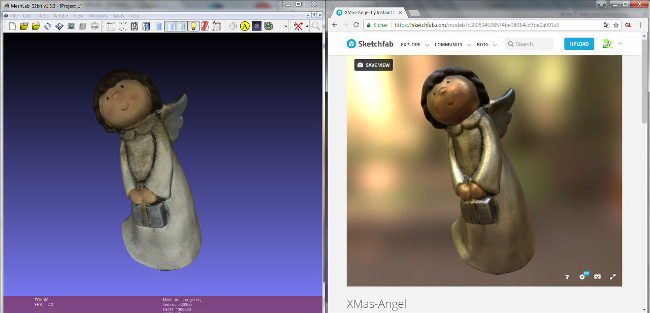

The small, decorative figure has been digitized a while ago by a 3D scanner at CultLab3D. Some years back, people would just be able to experience the 3D model with specialized Desktop software, such as MeshLab. Most people wouldn't know that this software even exist, and a decade ago most common PCs without a dedicated GPU wouldn't even have been able to render this model fluently. Finally, in order to access this model, one would have to download it, most likely as a large OBJ file, and then open it with some 3D viewer. A workflow that would for sure not be considered easy, or accessible, by most people.

In contrast to the Desktop workflow, accessing the model on Sketchfab, using a browser, is of course a tremendous improvement with regards to accessibility. Apart from that, if asked which version they would prefer, most people would probably state that the Sketchfab version looks much more appealing as well. This is mainly due to the great job the Sketchfab guys did when implementing a portable physically-based rendering (PBR) pipeline that works within all kinds of browsers: in contrast to the common Blinn/Phong shading model, which is still used by default within most traditional 3D Desktop applications, many modern, fresh 3D Web viewers provide much more recent, state-of-the art methods for rendering - in spite of the fact that the technical possibilities offered through WebGL were quite limited for a long time. And, yeah, with the standard Sketchfab viewer, you can even press a button on the page, put your smartphone-powered VR device on, and instantly view the 3D object in stereo - just as easy as that. This example was pretty simple, but I think it shows in a nutshell how much improvement in accessibility and quality of the whole 3D user experience has happened within the past few years.

Now, if you allow me a small personal note: I believe that, if we want to make more content generally available in 3D, we will need to make the reduction and compression of 3D assets as simple as it is for images nowadays. From the original one million triangles + texture (68 MB) used for the Desktop version of the above example, the Web version was optimized for faster loading down to less than six thousand triangles + textures (2.2 MB) via MOPS CLI, without a notable loss in visual quality. This is where my personal, tiny contribution to the whole piece comes in: Reducing the resolution of an image and saving it as JPEG is an absolute no-brainer, and it would be great if processing of 3D assets could become similarly easy and accessible to everyone. For sure, I am not the first to recognize this, or to provide a technology that helps to work towards that goal. For example, Microsoft acquired Simplygon, a highly successful, leading company in 3D optimization, earlier this year - in order to support the already mentioned 3D For Everyone strategy.

Conclusions

So, to sum it up, 3D content has already become much more accessible since the advent of WebGL. In addition, Microsoft's 3D For Everyone strategy will possibly in the end make 3D content just another useful, well-accepted type of media within many contexts, such as documents or slide shows. This means nothing less than that, for the first time, the technical possibilities for 3D content in day-to-day applications are really there. And with that said, I am, for now, allowing myself an optimistic look into the future of 3D technology within serious applications that could emerge outside the games market.

I am already looking forward to see what will happen within the next five years. And I am looking forward to hear your feedback! So, if you like, please feel free to write me a comment within the respective twitter thread - I would love to hear your opinion on this topic.

Other Articles

< Back to Articles section